Watching how people interact with an interface tells you a lot about what works and what needs improvement.

Watching how people interact with an interface tells you a lot about what works and what needs improvement.

And while observing behavior is essential for understanding the user experience, it’s not enough.

Just because a product does what it should, is priced right, and is reliable, doesn’t mean it provides a good user experience.

Users can think the experience is too complicated or difficult. For example, a lot of B2B software products, like expense reporting apps, meet the organization’s needs and are reliable but have a lot of steps and confusing jargon that make them quite unpleasant.

To have a good UX means understanding and measuring actions AND attitudes.

It’s about function, but also about feeling. Attitude not only describes how people feel while using an interface or interacting with a product, but it may also be the explanation for WHY people will or won’t use a product or app in the future.

If you want to understand and predict user behavior, you need to understand attitudes. But what is an attitude?

Three Parts to Attitude

An attitude is a disposition to respond favorably or unfavorably to a person, product, organization, or experience. People have positive and negative feelings and ideas about companies, websites, and experiences.

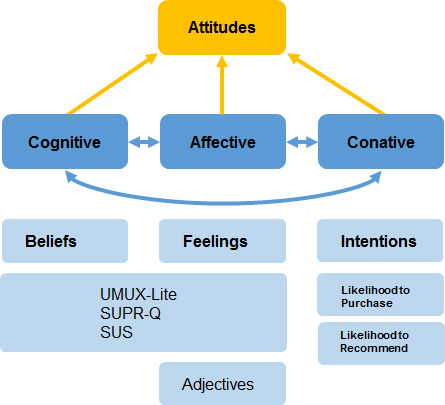

But similar to the concepts of UX and usability, attitude can be thought of as a multidimensional construct with related components. For decades, researchers in the social sciences have been modeling and measuring attitudes. While there is debate on how to best decompose attitude, one influential model is the tripartite model of attitude, also called the ABC model. Under this model, attitude is composed of three parts: cognitive, affective, and conative. It’s also referred to as affect, behavior, and cognition (hence ABC).

We can illustrate this concept using three things people are familiar with and likely have favorable and unfavorable attitudes toward: snakes and two brands (Apple and Facebook).

Cognitive: Beliefs people have about a brand, interface, or experience.

- Snakes control the rodent population.

- Apple makes innovative products.

- Apple’s products are very expensive.

- Facebook connects me with friends and family.

- Facebook presents ads based on my profile.

Affective: Feelings toward a brand, product, interface, or experience.

- Being around snakes make me feel tense.

- Apple products make the world a better place.

- Apple wants to squeeze as much money from me as possible.

- Facebook makes me feel closer to my family.

- Facebook is unfairly using my data.

Conative (Behavior): What people intend to do. Sometimes this is called behavior; I think that confuses it with actual behavior, but it does help with the ABC acronym.

- I will pick up a snake.

- I’m going to recommend my mom get the new iPhone.

- I’m not going to purchase another MacBook.

- I will post photos of our vacation on Facebook tonight.

- I’m going to boycott Facebook this month.

Under this tripartite model, attitudes can be thought of as beliefs, feelings, and intentions (see Figure 1). Each of these aspects of attitude typically correlates with the others. Positive beliefs about an experience or product tend to go along with positive attitudes and favorable intentions. But the correlation isn’t always high, so it can be helpful to separate them and understand how each of these components may lead to different behaviors.

For example, people can believe that Apple’s products are expensive (negative belief), think Apple cares about them (positive feeling), and intend to purchase and recommend its products (positive intention).

Measuring Attitudes

We can’t directly observe attitudes. Instead, we have to infer attitudes from what we can measure. While there are ways to measure nonverbal behavior (such as heart rate when in the presence of snakes), it’s usually a lot easier (and often as effective) to use self-reported measures. Rating scales from standardized questionnaires are the most common method. For the user experience, this can be the items on the SUS, SUPR-Q, UMUX-Lite, Net Promoter Score, and adjective lists (such as those in the Microsoft Desirability Toolkit). Here are ways to think about measuring each of the aspects of attitude.

Cognitive: Assess what users’ beliefs are using agree and disagree statements (such as 5-point Likert scales).

Apple’s products are expensive.

iTunes is easy to use. (Part of the SUS and UMUX-Lite)

It is easy to navigate within the Facebook website. (Part of the SUPR-Q)

Overall, the process of purchasing on Facebook Marketplace was very easy–very difficult. (Part of the SEQ)

Affective: Use adjective scales and agree/disagree scales to assess affect (SUPR-Q, SUS, satisfaction, Desirability Toolkit).

The information on Facebook is trustworthy. (SUPR-Q)

Which of the following best describes Apple? (Desirability Toolkit)

- Creative

- Cutting-edge

- Expensive

- Elite

- Inspiring

- Innovative

You’ll notice the considerable overlap between the use of scales for the cognitive and affective components of attitude—reinforcing their correlated nature.

Conative: Ask about future intent.

How likely are you to recommend Apple to a friend or colleague? (NPS)

I am likely to visit the Facebook website in the future. (SUPR-Q)

Figure 1 shows how to think about these aspects of attitude and how to measure them.

Figure 1: Three components of attitude and how to measure them.

Using Attitude to Predict Behavior

Decomposing attitude into these three parts helps describe the user experience but also may predict behavior. In our earlier analyses, we’ve found that attitudes toward the website user experience (accounting for both beliefs and feelings) predicted future purchasing behavior. There’s evidence that high satisfaction leads to greater levels of loyalty, buying intention, and ultimately buying.

We’ve also found that both beliefs and feelings (SUS) predicted intentions (NPS) (hence the arrows connecting these sub components in Figure 1). The Net Promoter Score (behavior intention) predicted growth in the software industry and correlated with future growth in 11 of 14 industries.

If you want to change behavior you need to understand and measure attitudes. If users find an experience difficult and/or a product expensive or lacking functions (cognitive), it will eventually lead to negative feelings (affect) and reduced intention to use and recommend (conative), and ultimately people will stop purchasing or using (behavior). We’ll explore this connection in a future article.

The actual change in behavior can take time and is affected by factors such as the presence of better alternatives and switching cost. But the story of Quark software may offer a good example of how cognition, affect, and intention combined with new competition led to behavioral change—and the fall of a once dominant product and company.

Summary and Takeaways

In this article, we considered the role of attitude in the user experience:

UX is both actions and attitudes. To understand a user experience, you need to account for both actions and attitudes. You can’t say a user experience is delightful or dreadful from observation alone. You need to understand how people think and feel.

There are three parts to attitude. An influential model of attitude decomposes it into three parts: cognitive, affective, and conative. It’s also called the ABC model (affective, behavioral, and cognitive) and means that attitude is comprised of what people believe (cognitive), how people feel (affective), and what they intend to do (conative/behavioral).

Measure attitude to understand UX. You can use common standardized questionnaires such as the SUS, UMUX-Lite, and SUPR-Q to measure the cognitive and affective components of attitude. Ask about future intent, likelihood to purchase, use, and recommend (Net Promoter Score) to assess the conative/behavioral component of attitude.

Attitude can explain and predict behavior. Understanding what people think and feel can help explain why people act and predict future behavior (such as purchase behavior), continued usage, and growth of products across industries.

from MeasuringU https://measuringu.com/ux-attitudes/