Of all the influences from the past 100 years, the Bauhaus—the venerable art and design school founded in 1919—has had the most enduring impact on the world, from the modern products and furniture we buy, to the graphics we see, and the architecture we inhabit. Yet while scholars have pored over the school and deconstructed its teachings for decades, many untold stories still wait to be unearthed.

This month, the Harvard Art Museum is highlighting them, launching a digital archive of its immense collection of Bauhaus-related artworks, prototypes, documents, prints, drawings, and photographs. The archive is the legacy of Bauhaus founder Walter Gropius, who became a professor at Harvard in 1937 after the school closed in 1933 (the Nazis did not agree with its experimental teachings), bringing his knowledge and ephemera to Cambridge, Massachusetts.

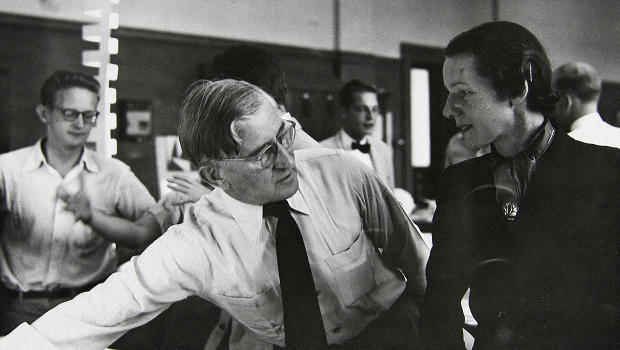

and Fellows of Harvard College]

The new microsite is a valuable design resource that makes the pieces accessible to the entire world. It’s intended to be a portal into the Bauhaus’s work and a study tool to help inform further scholarship into the institution’s legacy and impact. (In fact, Bauhaus superfans take note: anyone can make an appointment to view any of the holdings first-hand, assuming that they’re not on loan.) Robert Wiesenberger, a curatorial fellow at the museum, developed the online collection, which involved making sense of the 32,000 Bauhaus-related pieces in the collection: categorizing, interpreting, and adding just enough context to orient visitors to the site.

“First and foremost, the Bauhaus was a school of art and design—and it was filled with contradiction,” Wiesenberger says. “I really wanted to surface objects and provide a little context. Since there are already shelves and shelves of books about the Bauhaus, I didn’t want to regurgitate a history; however, if the subject is new to someone, there’s a primer.”

We asked Wiesenberger to share a handful of unexpected design lessons to be gleaned from Bauhaus objects in the Harvard Art Museum’s collection.

In the age of unlimited digital storage, it’s easy to forget that purposeful documentation is important. It’s more than just taking a snapshot on your camera phone as an afterthought—it’s about annotation and being conscious of what you’re recording in notes so that you can trace the development of an idea.

“Most of what we know of the Bauhaus’s output is from the photographs taken at the school,” Wiesenberger says. “The architecture changed, suffered damage, or was destroyed; though many of the products were intended for mass production, they often only ever existed as one-off prototypes or in limited quantities and have been lost along the way. Luckily, some Bauhäusler—the term for people attending and working at the Bauhaus—captured the school’s work photographically, both for artistic reasons and to help the Bauhaus commercialize what was made there.”

“The most brilliant of these artists was Lucia Moholy, the wife of Lázsló Moholy-Nagy, whose precise, dead-on depictions of objects are still some of the most-circulated images from the school. Yet even so-called ‘objective’ documentation is not neutral, either: Many decisions are made behind the camera, and Lucia’s name was effaced from the historical record in part by Walter Gropius, with whom she entrusted her negatives when she fled Germany.”

Few of us are diligent diarists; however keeping track of everything can help designers today—and in the future. If it weren’t for Lucia Moholy and her obsessive photography, we wouldn’t have as much knowledge of the Bauhaus since many of the physical objects are lost.

Everyone loves a rager, even the serious rationalists at the Bauhaus.

“The Bauhaus famously threw incredible parties,” Wiesenberger says. “For the ‘Metal Party’ in 1929, guests clad in shiny homemade costumes slid in on a chute beneath mirrored orbs hanging from the ceiling. Oskar Schlemmer’s stage workshop, and the metal workshop run by Marianne Brandt, were especially active in the planning. But it wasn’t all just fun and games: Walter Gropius, the school’s director, knew that parties were essential in letting off considerable steam for hard-working and often conflicting Bauhäusler, as the school was full of big personalities with big ideas who often locked horns. Parties helped everyone remember they were part of the same team.”

Design is rarely a solo endeavor and team-building can go a long way in helping to facilitate the conversations that may lead to a creative breakthrough.

Lázsló Moholy-Nagy—a painter, photographer, sculptor, and professor—headed up the Bauhaus’s metal workshop. In 1930, he designed Light Prop for An Electric Stage, which is currently on-view in a retrospective of his work at the Guggenheim Museum.

“It’s kind of an avant-garde disco ball, designed to create kaleidoscopic colored light effects,” Wiesenberger says. “But this, one of the Hungarian Constructivist’s proudest achievements, didn’t emerge from his head fully formed. Rather, he claims that the idea began its gestation in 1922, and it went through multiple versions before its first exhibition in Paris in 1930. But he wasn’t finished with it then, either, and he made many later alterations to optimize its ‘light-modulating’ effects, for example, substituting in matte or glossy pieces of metal.”

“The Light Prop was a new kind of art, made without the artist’s hand, and industrially fabricated like Minimalist art would be in the 1960s. Moholy-Nagy worked with two engineers to design and construct the device, which was built with funding from Germany’s AEG corporation. His name does not appear anywhere on it, but one engineer’s name, Otto Ball, does. Like Marcel Breuer’s iconic tubular steel club chair, which was first prototyped by a plumber, Moholy-Nagy, the ‘universal artist,’ still knew when to call on outside help.”

Just as Breuer and Moholy-Nagy looked to experts from different trades to fuel innovation, designers of today can stand to be open to collaboration from other fields rather than walling themselves off in their respective industries.

Contemporary design is notorious for established rules and having a base in function, research, testing, and strategy. Fantasy, as superfluous as it sounds, has a place, too.

“Paul Klee, born in Switzerland but seemingly from another planet, wasn’t an obvious choice as an instructor at the Bauhaus, a school dedicated to pragmatic design and building,” Wiesenberger says. “Of course the Bauhaus wasn’t always this way, and was founded on utopian ideals and the legacy of German expressionism, but Klee’s continued presence there—for a decade he taught form and color to entering students—was essential to the school’s character well after it dedicated itself to a ‘union of art and technology.’ Klee’s playful drawings channeled nature, poetry, architecture, music, and even magic—Apparatus for the Magnetic Treatment of Plants references the 18th century pseudoscientific idea of animal magnetism while lightly satirizing the machine. Klee enjoyed the reputation of a mystic—though he was certainly a rationalist—and his operating on an entirely different plane from the school’s functional program only enriched students’ experience at the Bauhaus.”

Perhaps the most poignant lesson: while today’s designers have access to advanced tools and materials, everyday surroundings and economy can fuel the next great idea.

“Ruth Asawa, a California-born Japanese-American artist, who learned drawing in a Japanese internment camp, went to Black Mountain College to study with former Bauhaus master Josef Albers,” Wiesenberger says. “Without money for art supplies—like Albers had been in his student days in Weimar—Asawa exemplified her mentor’s credo, of ‘minimal means, maximum effect.’ Like all students at Black Mountain, Asawa worked on campus to help the school run: While posted in the laundry room, she made rubber stamp drawings on newsprint. This one repeats the text ‘Double Sheet’— a double-meaning of both linen size and the folded-over newspaper format. This exemplifies Albers’s lessons of radical economy, transparency, positive and negative space, and the meandering patterns he gave as assignments. As a kind of typographic textile, these works anticipate Asawa’s more famous hanging wire sculptures.”

As we grapple with the need to be more resource efficient, the simplest things might end up having the greatest potential.

To see more of the collection, visit harvardartmuseums.org.

from Sidebar http://sidebar.io/out?url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.fastcodesign.com%2F3063102%2F5-timeless-design-lessons-from-the-bauhaus