How Fonts Are Fueling the Culture Wars

Pay attention: Typography isn’t just catchy visuals. It can also be dangerous.

Typography is undergoing a public renaissance. Typography usually strives to be invisible, but recently it’s become a mark of sophistication for readers to notice it and have an opinion.

Suddenly, people outside of the design profession seem to care about its many intricacies. Usually, this awareness focuses on execution. This year’s Oscars put visual hierarchy on the map. XKCD readers will never miss an opportunity to point out bad keming. And anyone on the internet can tell you, Comic Sans has become a joke.

But by focusing on the smaller gaffes, we’re missing the big picture. Typography is much bigger than a “gotcha” moment for the visually challenged. Typography can silently influence: It can signify dangerous ideas, normalize dictatorships, and sever broken nations. In some cases it may be a matter of life and death. And it can do this as powerfully as the words it depicts.

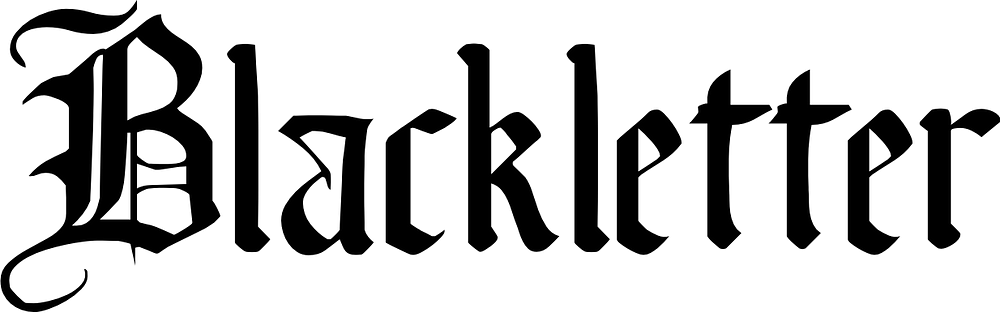

Why We’re Afraid of Blackletter

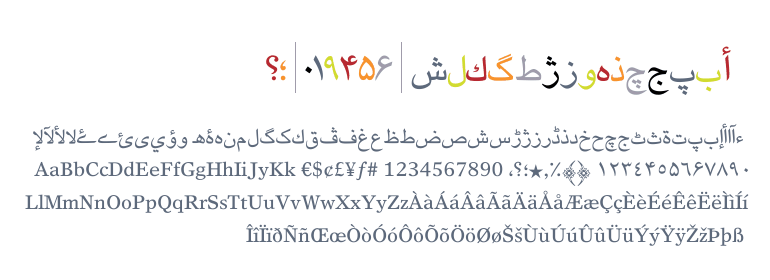

You’ve seen blackletter typography before. It’s dense, old-fashioned, and elaborate. It almost always feels like an anachronism. It looks like this:

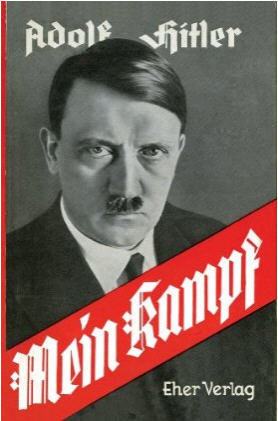

But usually when you see it in popular culture, it looks more like this:

Or like this:

You probably know blackletter as the script of choice for bad guys, prison tattoos, and black metal album art—and you wouldn’t be wrong.

Blackletter looks esoteric and illegible now, but it started off as a normal pattern that people across Europe used every day for hundreds of years. It stayed that way until pretty recently. A third of the original fonts at Monotype, the American company behind classics like Times New Roman and Gil Sans, were blackletter.

Why don’t we use blackletter anymore? The answer is literally “Hitler.” Nazi leadership used the Fraktur, an archetypal variety of blackletter, as their official typeface. They positioned it as a symbol of German national identity and denounced papers that printed with anything else.

As you might imagine, the typeface hasn’t aged well in the post-war period. In just a few years, blackletter went from ordinary to a widespread taboo—the same way the name “Adolf” and the toothbrush mustache have been all but eradicated.

The Nazis played a part in this. In 1941, the regime re-characterized Fraktur as Judenletter, “Jewish letters,” and systematically banned it from use. The long history of Jewish writers and printers had tainted the letterforms themselves, they argued, and it was time for Germany to move on. Historians speculate that the reversal had more to do with the logistics of occupying countries reliant on Latin typefaces, but the result was the same. No printed matter of any kind could use Fraktur, for German audiences or abroad. Even blackletter handwriting was banned from being taught in school.

Think about that: The government of one of the world’s great powers banned a typeface. That is the power of a symbol.

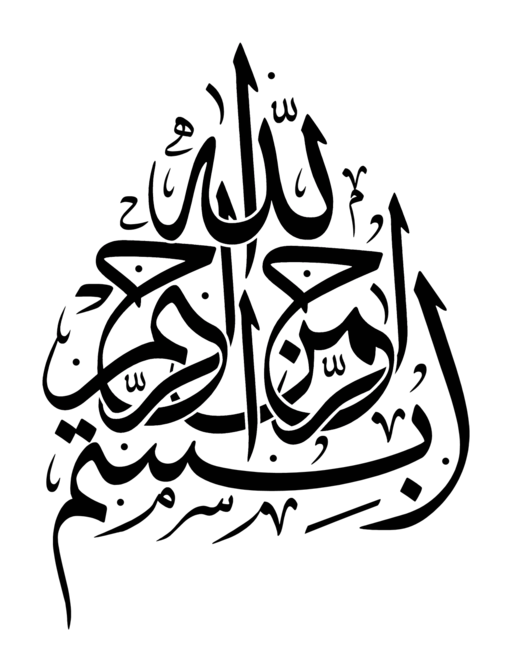

It’s Hard to Text in Arabic

We take it for granted that we can type any word with a keyboard, but really, you should check your anglophone privilege. In English, each letter stands on its own, while Arabic connects every letter in a word, allowing many letters to take on new shapes based on context. Arabic lends itself to lush and poetic calligraphy, but it doesn’t square with traditional European methods for making typefaces.

Much of the Arab world fell under Western colonial rule, and print communication remained a challenge. Rather than rethinking or expanding the conventions that had been designed around the Latin alphabet, the colonial powers changed Arabic. What we see in books and newspapers to this day is a ghost of Arabic script, reworked to use discrete letters that behave on a standard printing press.

It’s not surprising that colonial powers would pull their subjects closer to their center of gravity. But even today, many Arab countries struggle with that legacy. There are over 20,000 ways to format a word in English; the Arabic world only has about 100 clunky typefaces to support communication between half a billion people.

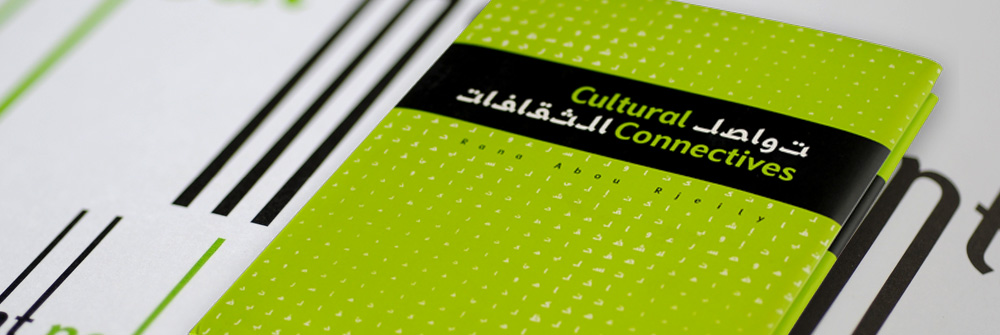

Rana Abou Rjeily, a contemporary Lebanese designer, is reclaiming Arabic typography. After studying design in the US and UK, she developed Mirsaal, an experimental typeface to bridge the gap between Arabic and Latin text.

Mirsaal looks for the right balance of western conventions to make Arabic work in a modern context. It uses simplified, distinct letterforms, but with the goal of making written Arabic more expressive and authentic.

This isn’t a purely symbolic exercise. The Middle East is dealing with political instability that stems from deep cultural divisions. It is not hard to imagine how a more robust written language might play some role in making a better future.

Piecing Together the Balkans

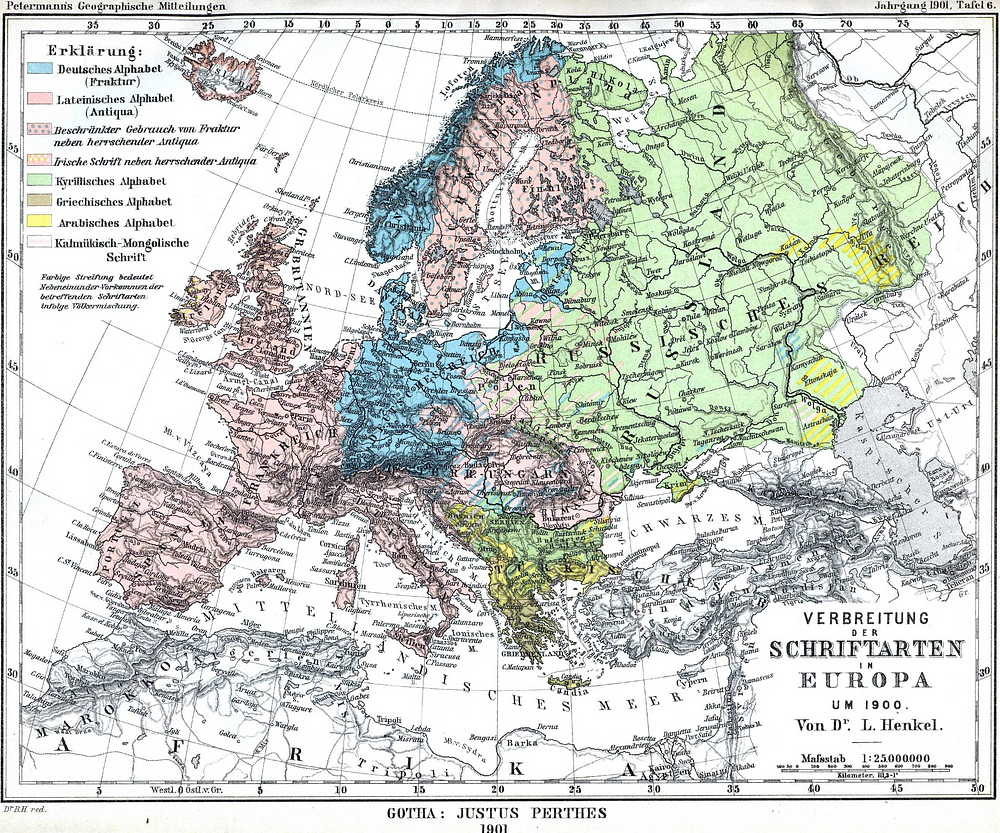

The Balkans are synonymous with fragmentation. The region has seen generations of violence, much spurred by the ethnic tensions within. Their typography reflects these divisions. The regional languages are a hodgepodge of typographic spheres: Latin, Blackletter, Cyrillic, and Arabic. Never mind the locally designed Glagolitic scripts.

Typography took on special meaning during the Cold War, as Latin and Cyrillic alphabets came to symbolize allegiance to global powers.

Since the fall of the Soviet Union, typography continues to communicate political leanings, be they nostalgia for the Soviet era or alignment with the globalized West. Using the wrong typeface could get you in a lot of trouble.

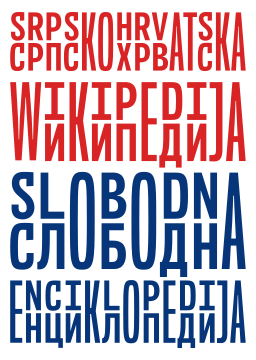

In 2013, Croatian designers Nikola Djurek and Marija Juza created the East-West hybrid Balkan Sans. Balkan Sans uses the same glyphs to represent the equivalent letters in Latin and Cyrillic alphabets. In the words of its makers, it “… demystifies, depoliticizes, and reconciles them for the sake of education, tolerance, and, above all, communication.”

Croatian and Serbian are similar languages that could hardly look more different in their written forms. Balkan Sans makes them mutually intelligible, so that two neighbors might be able to correspond over email without thinking twice. They transformed typography from a barrier between nations into an olive branch.

The Culture War at Home

The US is not so different from the rest of the world when it comes to tribalism and conflicted identity. This has crystalized in last few months, and we’ve seen typography play a substantial role.

Hillary Clinton ran for president with a slick logo befitting a Fortune 100 company. It had detractors, but I think we’ll remember it fondly as a symbol of what could have been — clarity, professionalism, and restraint.

Donald Trump countered with a garish baseball cap that looked like it had been designed in a Google Doc by the man himself. This proved to be an effective way of selling Trump’s unique brand.

I’m not interested in whether Clinton or Trump had good logos. I’m interested in the different values they reveal. Clinton’s typography embodies the spirit of modernism and enlightenment values. It was designed to appeal to smart, progressive people who like visual puns. They appreciate the serendipity of an arrow that completes a lettermark while also symbolizing progress. In other words, coastal elites who like “design.”

Trump’s typography speaks with a more primal, and seemingly earnest voice. “Make America Great Again” symbolizes “Make America Great Again.” It tells everyone what team you’re on, and what you believe in. Period. It speaks to a distrust of “clean” corporate aesthetics and snobs who think they’re better than Times New Roman on a baseball cap. Its mere existence is a political statement.

The two typographies are mutually intelligible at first glance, but a lot gets lost in translation. We live in a divided country, split on typographic lines as cleanly as the Serbs and the Croats.

I’d Like to Leave You With a Mission:

The next time you go shopping, download an app or send an email, take a second to look at the typography in front of you. Don’t evaluate it. Don’t critique it. Just observe it. What does it say about you? What does it say about the world you live in?

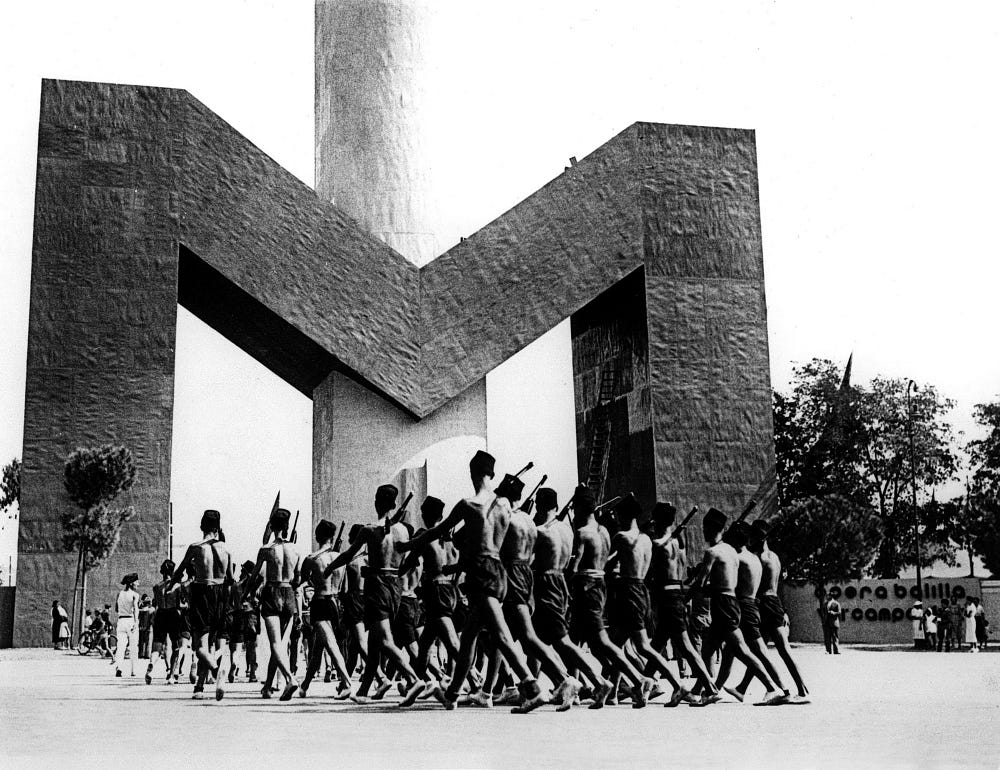

The stakes are higher than you think. The next generation of fascists will not love geometric sans serifs as much as Mussolini did. They won’t be threatening journalists in blackletter.

The world is changing around us. We constantly debate and analyze the conflicts between the militaries, governments and cultures that surround us. But there’s a visual war that’s happening right in front of our eyes, undetected. Its power — to divide us or bring us together — hinges on our choice to pay attention.

from Sidebar http://sidebar.io/out?url=https%3A%2F%2Fbackchannel.com%2Fhow-fonts-are-fueling-the-culture-wars-f9d692101fea