Finding and fixing problems encountered by participants through usability testing generally leads to a better user experience.

Finding and fixing problems encountered by participants through usability testing generally leads to a better user experience.

But not all participants are created equal. One of the major differentiating characteristics is prior experience.

People with more experience tend to perform more tasks successfully, more quickly and generally have a more positive attitude about the experience than inexperienced people.

But does testing with experienced users lead to uncovering fewer problems or different problems than with novices? As participants gain experience with an app do they find workarounds that mean problems are less detectable in usability tests? Or do expert users tend to uncover the same or even more issues because of their knowledge of the app?

Defining Experience

For quite some time there has been a discussion on the differences between novice and experienced users. For example, in Nielsen’s seminal book, Usability Engineering, he defines three types of experience levels that are worth noting:

- Domain knowledge: Ignorant versus knowledgeable

- Computer knowledge: Minimal versus extensive

- System knowledge: Novice versus expert

While there’s general agreement that domain, tech, and app-specific experience are the aspects that separate novices from experts, it’s less clear what those thresholds are. For example, Dumas and Redish provide the general guidance of:

- Novice: < 3 months of experience

- Intermediate: > 3 months but < 1 year of experience

- Expert: > 1 year experience

And Hackos and Redish (1998) identify four levels of expertise:

- Novices: New users of a product (e.g. using an information kiosk at a museum or airport)

- Advanced beginners: Focus on getting job done (e.g. most people’s use of microwave ovens)

- Competent performers: Ability to perform more complex tasks (e.g. computer repair technician)

- Expert performers: Have a comprehensive understanding of the whole system (teach the support technicians)

Differences in Problems Uncovered Between Experts and Novices

While there is variation in how experts and novices are differentiated, I reviewed the literature to look for studies that compared the two, however they are defined. In particular, I looked for any evidence that experts and novices encountered a different number, severity, or type of usability issue.

Experts Finding More Problems than Novices

Two studies found experts uncovered more problems than novices.

Prümper et al. (1991) observed 174 clerical workers working on their own computers and recorded errors. Experts were defined as having at least one year of computer expertise, familiarity with one program, and using a computer at least 50% of the day (something similar to the Nielsen 3).

In this observational study (rather than usability evaluation), counterintuitively, they found expert users committed more errors than novices but experts spent less time handling the errors than novices. This is in line with Don Norman’s distinction between mistakes (an error in the intention) and slips an error in carrying out the correct intention). Both novices and experts would be expected to make slips, but experts may commit more slips because they’re working faster, and due to their expertise, have developed strategies for quickly recovering from slips.

Sauer et al. (2010) had 48 participants interact with a floor scrubbing prototype or product. Half were experts (used the device at least once per month) and half were novice (never having used). They found that experts identified more usability problems than novices (157 vs. 109). After removing duplicates, they were left with 116 distinct problems, of which 56% were identified by experts, 8.6% by novices, and 35.3% by members of both groups. Usability problems reported by novices were considered to be more severe than those identified by experts.

The authors noted that experts reported more potential problems due to their higher level of expertise, which allowed them to anticipate usability problems that may occur in task scenarios they had previously experienced. They advised that if the primary goal is to identify the most severe usability problems as quickly as possible, there seem to be some benefit of relying on novices rather than experts. But they also recommended including self-reported usability problems as a measure, especially if there is a wide range of possible task scenarios that can’t be covered in a usability test.

Novices Finding More Problems than Experts

Five studies found novices uncovered more problems than experts.

Bourie et al (1997) observed 10 nurses using an online patient assessment application. Novice usage was three weeks with the system versus 1.5 to 3 years for experts. The authors described novice users having more problems with the system than the experts (although the number and severity weren’t specified).

Donker and Reitsma (2004) tested 70 Dutch kindergarteners and first graders on an educational reading software program. Experts were children who had been using the software three times a week for at least three months or two times a week for six months. They reported novice children encountered more problems than experts while using educational software.

Gerardo (2007) had 23 Norwegian participants attempt 14 tasks in an ERP system for small to medium businesses. The 12 experts in the study had used the system before, but were unfamiliar with the new interface. In contrast, the 11 novices had no experience with the current product but had used a competing product for years (they had domain experience but not specific product experience).

The author reported novice users revealed more usability problems than experts and concluded that:

“It is therefore likely that the expert user’s usability problems will be detected through the use of novice users in usability tests. If a usability practitioner has to prioritize between recruiting novices and experts for a usability test after a major redesign, the practitioner will gain more by recruiting novice users.”

Faulkner and Wick (2005), in a study of 60 participants attempting tasks on a timesheet application, recorded user deviations from intended actions. These deviations were interpreted as symptoms of usability issues.

The authors differentiated between application experience and computer experience with three levels:

- Novice/novice: < 1 year of computer experience, no application experience

- Expert/novice: > 1 year experience using computers, no application experience

- Expert/expert: > 1 year experience using computers, > 1 year using the application

They reported novices committed three times more deviations from the optimal path than experts (66 vs 19).

Kjeldskov et al. (2005) had 7 nurses in Denmark use an electronic patient record system in a usability evaluation. 15 months later the same nurses who had been using the system extensively participated again in a usability evaluation with the same tasks. They found that novices generally encountered more usability problems: 93% vs 70% critical and 80% vs. 61% severe for novices and experts respectively.

While not a usability study, Shluzas et al (2013) asked 18 nurses to specify requirements of a drug delivery system [pdf]. Novices in the study had some experience with injections compared to experts who had substantially more (about 6 months vs. 17 years of experience). They found novice users cited requirements associated with product usability over two times as often as did expert users (39.4% vs. 17.1%), and experts cited requirements associated with product functionality over two times as often as did novices (35.4% vs. 16.7%). This suggested a different view of potential problems.

Experts vs Novices in a Social Media Usability Test

While we conduct studies regularly at MeasuringU, few studies directly compare novice and experienced users in the same study. A study we recently conducted on a social media platform examined the differences in usability issues between five expert (“power”) high-tech users and five novice, low-frequency, low-tech users. In this study, technical savviness and application experience were combined into one level, similar to the Faulkner and Wick combination. The novice participants, in this case, had some familiarity with the system (accessing only a few times per year) but lacked knowledge of common tech terms. Experts used the system daily and were familiar with all technical terms.

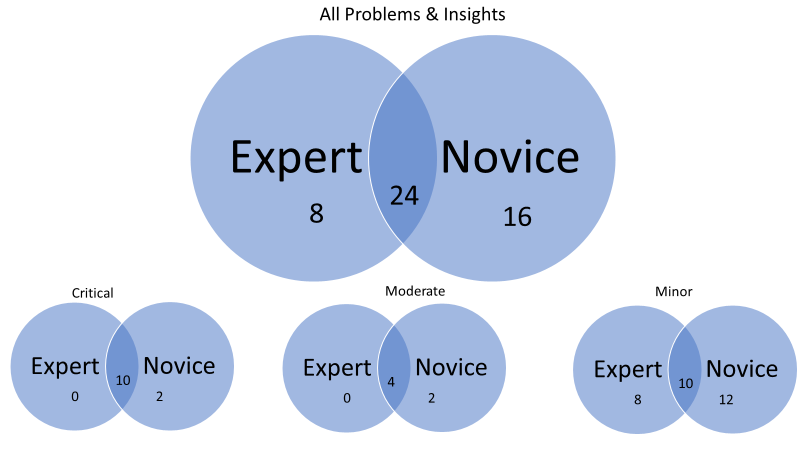

A total of 48 insights and problems were observed among the 10 participants. Novice participants encountered 40 (83%) of the issues and experts 32 (67%) of issues. There was a good overlap in issues between the groups as shown in Figure 1. Novices and experts both encountered 24 (50%) issues at least once. For unique issues, novices encountered 16 problems/insights experts didn’t, and experts encountered 8 that novices did not.

Figure 1: Overlap in problems found between expert and novice users on a social media platform.

Problems were also rated on a three-point severity scale as shown in Figure 1:

- Minor: Possible hesitation as participant attempts task, as well as slight irritation (30 issues)

- Moderate: Causes occasional task failure for some participants and moderate irritation (6 issues)

- Critical: Leads to task failure; causes participant extreme irritation (12 issues)

A similar pattern was seen across all levels of severity where novices uncovered problems experts didn’t critical (2), moderate (2), and minor (12). Experts uncovered 8 minor issues novices did not, showing that including both novice and experts provides a more holistic view.

In short, novices encountered more total problems/insights compared to experts and almost twice as many unique issues that experts didn’t.

Summary & Takeaways

A review of the literature and the study we conducted on experts and novices revealed a few things.

- Novices likely will uncover more issues, but not always. Of the 8 studies reviewed, 6 showed that novices uncovered more usability issues than experts. In many cases, novices also uncovered more severe usability issues than experts.

- The distinction between novice and expert is fluid. While there is general agreement that both knowledge and frequency of use differentiate experts and novices, there is less agreement on what the right duration and knowledge thresholds are. Despite the conventions by Dumas and Redish, differences can be days or years. This isn’t necessarily a bad thing, as the context will often dictate the delineation.

- Use both novices and experts for a holistic view of the experience. The evidence suggests that both novices and experts bring perspectives that aren’t necessarily an easy substitute for each other. Some studies (including ours) showed experts uncovered issues novices did not. If possible, include both novices and experts when looking to uncover the most usability issues.

- If testing with only experts, consider encouraging experts to articulate problems they foresee novice participants having. The expert user’s mental model and understanding of the software may allow them to identify potential trouble points.

- Small sample sizes may mask patterns, but meta-analysis helps. As is the case with other research (e.g. overlap in problems between HE & UT and the evaluator effect) the studies reviewed here generally have smaller sample sizes and reduce the opportunity to uncover similarities or differences between novices and experts. However, by looking across studies (a meta-analytic technique) you can look for patterns that single studies may not uncover. In this case, the pattern was generally that novices uncover more usability issues than experts.

Thanks to Jim Lewis for commenting on an earlier version of this draft.

from MeasuringU https://measuringu.com/novice-expert-issues/