Role-based Personas

Role-based personas derive from quantitative data and resemble the customer segments from more traditional market-research practices. Many usability professionals feel that these lack substantive information on the user’s thought processes and are overly reliant on modeling demographics on top of analytics. Personas are capable of answering what questions—for example: “What potentially meaningful patterns exist among our user population?” However, they fail to pursue the why questions. Just because we understand that a pattern actually exists, that does not necessarily mean we understood why it exists. While some UX professionals are comfortable speaking to why answers that are based solely on quantitative data, they typically frame these interpretations as being nothing more than reasonable, logical conclusions. However, these findings are vulnerable to confirmation bias because the conclusions depend so heavily on the researcher’s speculations.

Fictional Personas, or Proto-Personas

Fictional personas, or proto-personas, are based not on user research or feedback, but on the assumptions, anecdotes, and other past experiences of stakeholders and team members regarding users’ needs. While most UX professionals consider such personas to be flawed, the extent of their flaws and the purposes for which you could reasonably use them are less clear. Some UX professionals think teams should create proto-personas only as an exercise to promote thinking about the user as an individual who is different from oneself. Others think they can provide a useful starting point for generating hypotheses about users’ motivations and inclinations, which they would then validate through empirical observation. Critics think the act of creating proto-personas and the time and effort teams put into fleshing them out during such an exercise is toxic. That it creates an inescapable well of groupthink and results in other forms of bias that prevent related empirical-research efforts from moving forward.

Goal-Directed Personas

Goal-directed personas are most similar to the JTBD perspective. Focusing on the users’ goals is semantically similar to focusing on desired outcomes. However, despite their being goal directed, the personas themselves typically remain focused on creating a model of the users’ attributes. The goals typically diminish in importance because most of the researchers’ energy becomes entrenched in elaborating on the persona’s distinct motivations and needs. In the parlance of JTBD, focusing on job drivers, while giving little thought to success criteria stunts the persona’s growth.

A significant part of this fixation on attributes results from the focus on adding vivid details and stories to personas, which tend to be elaborate depictions of full personalities, having complete experiences, in the hope of making the personas feel real and relatable. The desire for personas to feel real and relatable is understandable and even admirable. Unfortunately, attempting to create that sense of reality by making personas feel like real people inherently turns them into something they were never meant to be. As I stated earlier, personas are aggregated proxies for groups of real-world users that represent their mental states and behavioral inclinations within a specific setting. Personas represent interconnected themes that occur within some meaningful, shared timeframe. Treating them as anything more becomes dangerously reductive. Personas do not have full personalities. Nor can they have complete experiences. Only people have full personalities and complete experiences. Personas are not people.

False Assumptions About Categorical Exclusivity

One of the most trying aspects of using personas in the workplace is having a stakeholder or team member walk up to you, with a part of the designed experience in hand, and asking, “Which personas are hitting this touchpoint?” or “Which personas are of critical concern during this part of the experience?” These kinds of questions are frustrating because personas don’t experience our products. People do.

Personas are neat, simple constructions that we pin to our walls. A Pragmatic Patrick is not a Dreaming Daniel and is never going to be. People are messy. They are fluid and fuzzy. A person can start a research and shopping journey as a Dreaming Daniel, then become more like a Pragmatic Patrick as they approach a purchase decision. They can be partly one persona and partly another. Such overlapping states could happen either sequentially or concurrently. The value of personas does not come from asking who is doing what, because a persona is not a who. Their value comes from knowing what mental states and behavioral patterns exist and considering them in all their potential forms. Different users can strongly manifest different personas at different moments, requiring different interpretations of their experience from the same stimulus on subsequent exposures.

I’ll illustrate this with an example: Recently, I was engaged in a research effort. We knew that two similar behavioral patterns existed that led to similar outcomes—at least from our perspective. We needed to learn whether consumers perceived these patterns and outcomes to be similar as well. Could the same workflow satisfy both behavioral patterns A and behavioral patterns B, or were these sets of behaviors sufficiently different from the consumer’s viewpoint to necessitate two semantically discrete pathways?

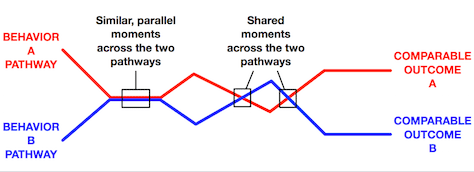

We found that consumers perceived the two sets of behaviors as being meaningfully distinct from one another and required different pathways. However, their following one pathway versus the other could be extremely variable. What’s more, many of the touchpoints along these discrete pathways either crossed over one another—creating a shared moment on the two pathways—or required some similar mimicry of comparable, parallel moments across the two pathways. Explicit signposts would be necessary to suggest how you might tailor actions along these touchpoints to either A or B behavioral inclinations and motivations, as shown Figure 1.

Our findings were admittedly complex. In our early drafts of the results, it became clear that one specific issue was making it more difficult for our stakeholders and team members to comfortably come to terms with the learnings. They kept talking about A Shoppers versus B Shoppers. With all the discussion of two comparable sets of behaviors and two comparable pathways, the team felt the need to understand consumers moving down those pathways as two categorically distinctive groups of people. However, this rigidity and perceived categorical exclusivity made it more difficult for the team to understand the complex, interwoven relationships between the two pathways. These were not two roller coasters on entirely separate tracks that were simply near one another. They were two different trains that occasionally shared the same track, with railway switches separating and crossing their pathways at various decision points. To understand the true relationships between these two pathways and the two sets of behavioral inclinations, we needed to understand that the actual people moving through these pathways were dynamically more complex than passive passengers on a static course.

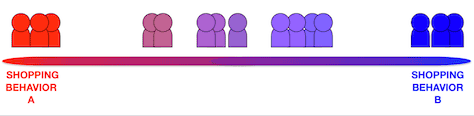

Imagine a spectrum with Shopping Behavior A on the left and Shopping Behavior B on the right, as shown in Figure 2. There were research participants who demonstrated strong tendencies toward the two extremes, and there were participants who demonstrated tendencies toward the middle ground between them.

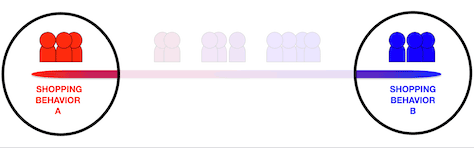

Individuals at the two extremes were categorically dissimilar from each other. They wanted different things and were going about getting them in different ways, as shown in Figure 3. Whatever combination of individual and situational variables added up to their cumulative past experience made them less likely to deviate from those extremes.

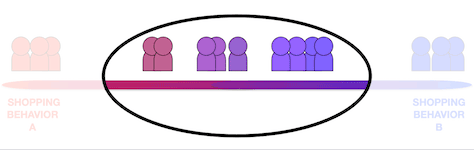

Individuals nearer the midpoint between the two extremes were more complicated. Sometimes they wanted different things and were going about getting them in similar ways. Sometimes they wanted similar things, but went about getting them in different ways, as shown in Figure 4. The individual and situational variables adding up to their cumulative past experience had less of a polarizing effect in comparison to that of the participants at the extremes. Instigating movement in one direction or the other was easier and far more likely.

Any given person has the equivalent potential of behaving either like a category member or a fluid, dynamic point, shifting along a spectrum. Thus, a population inherently does both at the same time. This idea might seem painfully obtuse and academic at first glance. However, a compelling simplicity is inherent in this idea that has huge tactical value—similar to learning that light behaves both like a particle and wave. When working with light, we have to make decisions considering all of the rules that apply, at all times.

Our stakeholders and team members needed to acknowledge that, to create an experience that complemented both of these pathways, the pathways had to be functional for both categorically static and spectrally fluid individuals simultaneously. To make that possible, we needed to create effective signposts that communicated accurate expectations, successfully execute our progressive-disclosure strategies, and follow other UX-design best practices. The only prediction we could reasonably make was that these meaningfully recurring patterns exist and, in most instances, we needed to attend consistently to both of them throughout the designed experience. Moments of addressing one pattern singularly and ignoring the other would be exceedingly rare—if they existed at all.

The sort of dilemma I’ve described is an inherent difficulty from which all personas suffer. Personas represent clusters of thought processes and behavioral inclinations co-occurring in the same moments of time, and we should almost always treat them as though they are simultaneously categorical and spectral. Any given data point that represents a person within an experience could actually be straddling two different personas—emphasizing or de-emphasizing each of them in turn or entering or exiting them entirely.

JTBD is better at fostering this understanding because it does not attempt to differentiate patterns that are based on people. This approach makes no claims regarding who might be thinking this thought versus that thought, nor who might be taking this action versus that action. It simply recognizes that certain thoughts and actions exist, in various forms, and that we need to attend to all of them because they all influence the user’s perception of progress toward the desired outcomes. The only reason ever to differentiate any of these patterns from one another in JTBD is when there is a dichotomy that is based on separate desired outcomes—not different users.

Conclusion

In summary, the attraction of using personas is undoubtedly powerful. The level of understanding that they seemingly promise is seductive. However, by their very nature, personas are exceedingly difficult to create and just as difficult to use. The construction and creation of a set of personas lacks a foundational methodology that has clear, operational definitions.

The primary focus of personas is summarizing complex, abstract concepts by meaningfully defining and clustering attributes that correspond to particular behavioral patterns. However, this focus on clustered themes that center on a representational archetype fosters a false expectation of true categorical consistency with real populations. Using personas is inherently risky because it increases the likelihood that reductive, simplistic thinking and assumptions might dictate design decision making.

JTBD offers a simpler solution that focuses on concrete concepts such as success criteria and avoids the unnecessary complexity of trying to model converging themes of thoughts and behaviors for anything beyond the user’s explicitly desired goals.

References

Block, Melissa. “How the Myers-Briggs Personality Test Began in a Mother’s Living Room Lab.” NPR, September 22, 2018. Retrieved February 12, 2019.

Boyle, Gregory J.“Myers-Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI): Some Psychometric Limitations.” (PDF) Bond University, March 1, 1995. Retrieved February 12, 2019.

Dam, Rikke, and Teo Siang. “Personas: A Simple Introduction.” Interaction Design Foundation, January 2019. Retrieved February 12, 2019.

Emre, Merve. The Personality Brokers: The Strange History of Myers-Briggs and the Birth of Personality Testing. New York: Doubleday, 2018.

Flaherty, Kim. “Why Personas Fail.” Nielsen Norman Group, January 28, 2018. Retrieved February 12, 2019.

Grant, Adam. “Goodbye to MBTI, the Fad That Won’t Die.” Psychology Today, September 18, 2013. Retrieved February 12, 2019.

Mulder, Steve, and Ziv Yaar. The User Is Always Right: A Practical Guide to Creating and Using Personas for the Web. Berkeley, CA: New Riders Press, 2006.

Nielsen, Lene. “Personas.” The Encyclopedia of Human-Computer Interaction, Second ed. Interaction Design Foundation, 2013. Retrieved February 12, 2019.

Reynierse, James H. “The Case Against Type Dynamics.” (PDF) Journal of Psychological Type, January 2009. Retrieved February 12, 2019.

Spence, Janet T., Robert L. Helmreich, and Robert S. Pred. “Impatience Versus Achievement Strivings in the Type A Pattern: Differential Effects on Students’ Health and Academic Achievement.” Journal of Applied Psychology, December 1987.

Wilkie, Dana. “How Reliable Are Personality Tests?” Society for Human Resource Management, September 11, 2013. Retrieved February 12, 2019.

from UXmatters https://www.uxmatters.com/mt/archives/2019/02/the-pitfalls-of-personas-and-advantages-of-jobs-to-be-done.php