TL;DR — Teams rush to build ‘low hanging fruit’, features they think will benefit users but also make them feel their achieving things. However, this is a mistaken belief that outputs equate to outcomes. But its almost as fast if you focus on the areas of highest value to your users and start by immediately delivering a small slice of that. You’ll end up delivering software just as quickly, which is a first step in making something truly great.

This was originally a presentation I made to several design teams, describing the benefit of moving away from delivering product features and towards addressing the most impactful user issues that we were finding in our research. It was a reaction to managing several design teams that often had their goal post’s moved during the year. I felt there were growing frustrations from teams that were struggling to make things they felt were valuable.

In this changeable environment, they looked for ways they could quickly feel the glow of satisfaction when progress is being achieved. Combined with a changeable company strategy, teams looked for ‘quick wins’ to help prove efficacy (to both themselves and others in the organisation) in the new space they were told to operate in. This post was a response to delivering on the ‘low hanging [feature] fruit’. My point was that to be ‘Quick’ doesn’t mean you just start with the easy, obvious things, that are plucked with no strategic value.

This was never meant as a “this is the only way to do it” polemic. I was a design manager working across several multi-disciplinary product teams and wanted to communicate a supportive message that doing high-value work is what we’re here to do. That I was here to help move towards identifying areas of greatest opportunity and then do work to address that.

Note: Names here are changed to protect the innocent. By that, I mean companies and teams I have worked with.

Features over value

Designing features is a common way that many software teams think about what they need to make. In many cases, features appear like a 1:1 match for an identified user need. In some cases it’s a literal response: User says this, we build this. However, this approach is hit and miss and also is in opposition to a systematic way that consistently produces solid products over a long period. Yes, it can work, but will the team produce and deliver value that builds on or creates sustained changes in user behaviour? Over time?

Feature focus tends to produce software products that are poorly conceived (doesn’t match users needs well), lack continuity (poor experience) and most importantly, don’t address fundamental behaviours that make our product and services useful and valuable to our users.

It often reflects organisations that are racing to deliver, that prioritises ‘shipping’ over ‘shipping value’ and measures their output through metrics that reflect activity (burn downs) rather than outcomes that reflect changes in user behaviour (behavioural metrics). I am not saying there is not a space for any of that, but for the maturity of the organisation we were in, I felt that this was not the place.

So….another way to look at this is to reframe the issue from the product perspective and ask the question: how will we know we’re doing a good job?

This is how we framed it:

Our products are loved when they continually and consistently fulfil the high-value need(s) of our users. We will know when we’re succeeding at this when we see a corresponding change in user behaviour.

Value and Outcomes

At this point, it’s worth talking about what I mean by value and outcome. These key terms describe not only the benefit of what you’re making but the change in user behaviour that occurs. Firstly, value, in this sense, is the scale of a (potentially unmet) behavioural need in our users. At my last company, Babylon Health, we knew that reducing the time that clinicians spent entering data into the EHR took time and attention away from their patients. It effectively reduced their effectiveness as clinicians and reducing that clerical burden is high-value for both clinicians and patients.

An Outcome is a change in user behaviour that we know drives business results. This definition is taken from ‘Outcomes over Outputs’, and stresses the symbiotic relationship between the organisational benefit that comes from changes in user behaviour that the products or service creates that change. An outcome, using the Babylon example, would be a reduction in time spent entering clinical notes into the electronic health record. The hypothesis here is that reduced time spent entering data meant more time spent engaging and understanding their patients.

At Babylon, we spent a lot of time mapping out these outcomes as a way of understanding what are the behaviours we want to change and what behaviours will we see that will help us know we’re on the right path. We looked to reduce time spent at the keyboard, to improve data entry tools and use AI and NLP to take over the clerical burden of a consultation.

Mapping areas of value

So instead of just continually adding features to our product or service, we should try and reframe the problem so we’re focused on areas of opportunity. The question is not ‘let’s add this feature’ (to a product rammed with features) it’s more ‘let’s find areas where we think we can add value/change behaviour’.

This is a reframing of the question, from ‘what should we build next?’ to ‘what problem should we try to solve?’. It’s a subtle difference in approach and in a world of making software, its easy to get them mixed up as you’re still delivering software. The difference is really an area of opportunity could have many solutions, often delivered in combination, that addresses a behavioural need…and sometimes could also not be software and located anywhere along the value chain. Whereas a feature tends to be viewed as a chunk of code that drives an isolated benefit.

So…What we define as ‘areas of opportunity’ typically emerge through our generative research and are formed as a result of deep understanding of our users, user behaviour and the problem space we are working in.

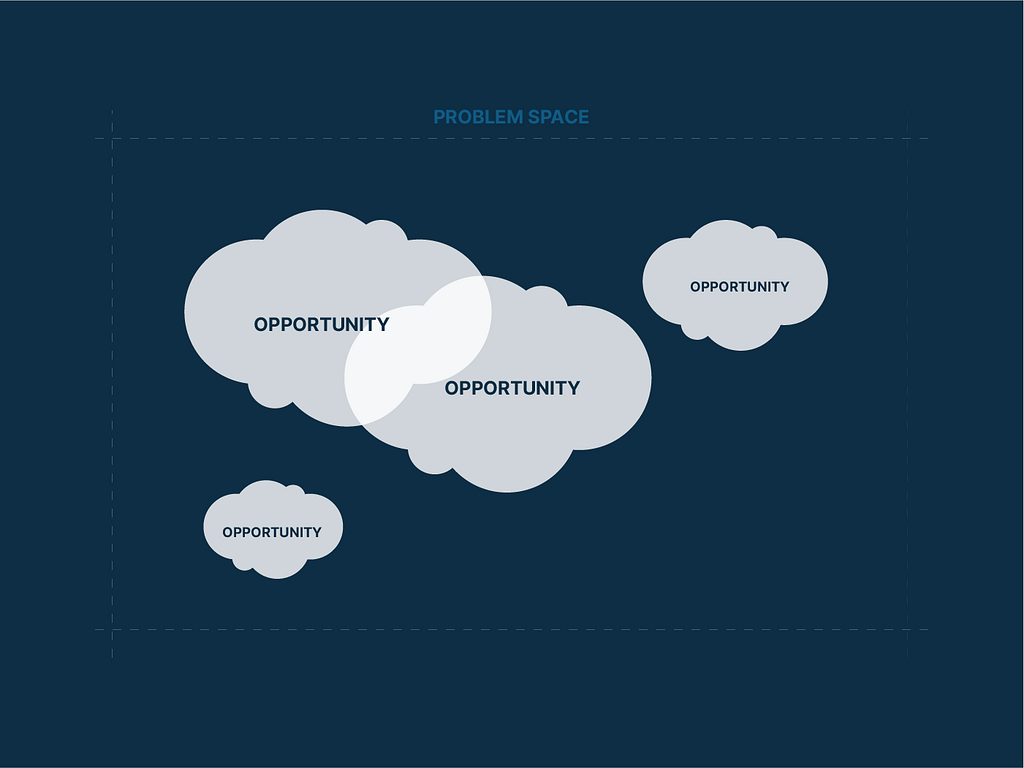

Often within a problem space, teams may identify many areas of opportunity and these areas even over-lap.

This is where continuous generative research identifies many of these areas of opportunity. Part of a team’s research activity is to constantly define, refine and add colour to these areas. This upward curve of understanding also highlights the behaviours around this opportunity we want to change. Teresa Torres refers to this as continuous discovery, an approach that looks to consistently identify areas of high value for users and fold that knowledge back into the product design process.

I can’t stress enough how important the nuanced view that emerges through continual research, helps create sublime products. I also can’t stress how important it is for design management/leadership to help give the space for teams to do this.

A bit about mapping and low hanging fruit

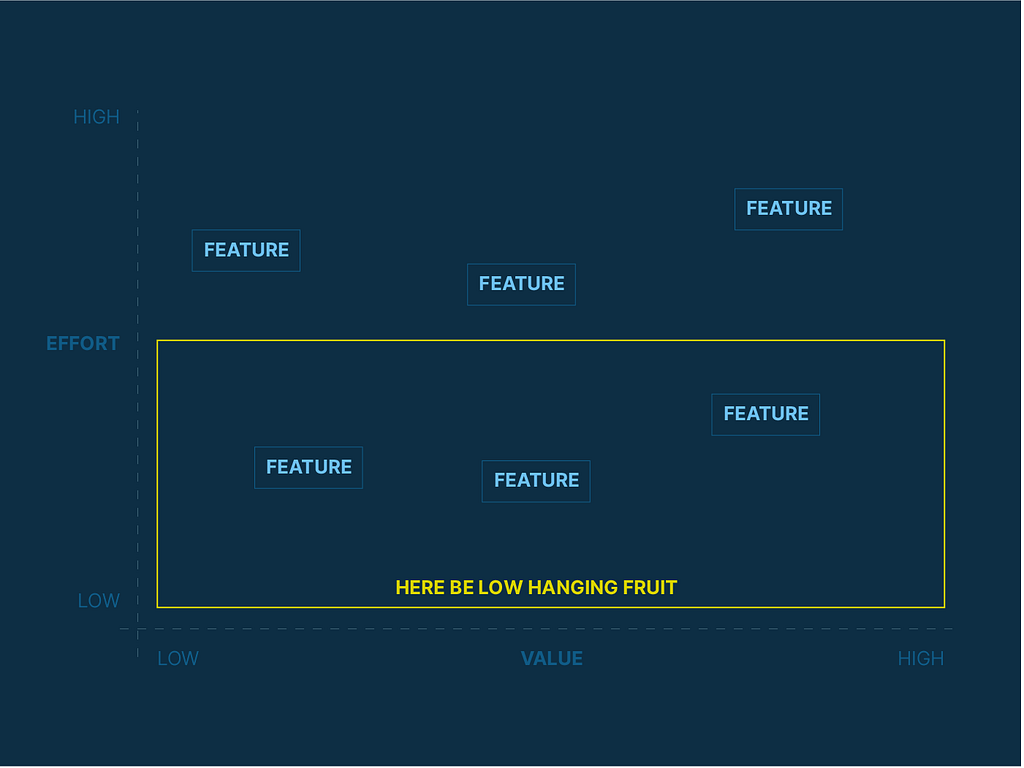

As hinted at earlier, The thing is mapping features and mapping areas of opportunity, is that they can look pretty similar.

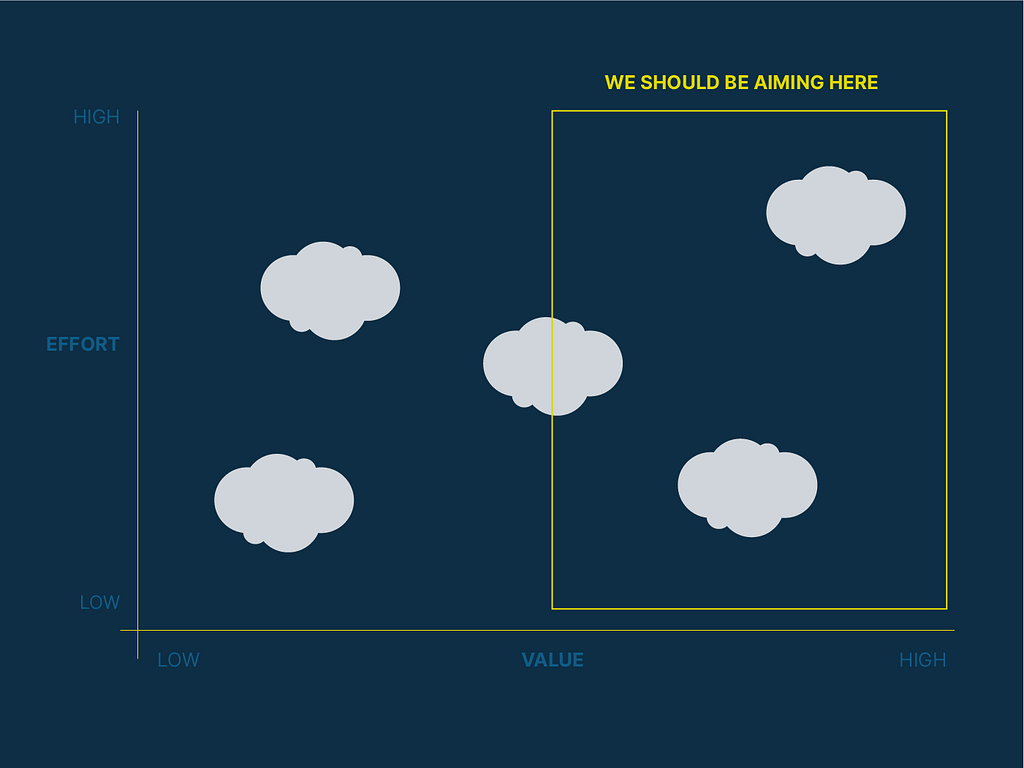

When looking at features, a filter of effort and impact can be used to rank each one. Especially in high delivery pressure environments, teams are often asking themselves ‘what can do straight away that we think will deliver value’ and in a feature-focus world, it’s easy to understand why low effort tasks tend to get higher priority. It’s probably the easiest way teams can show efficacy and impact.

The diagram describes the situation of the low-hanging fruit. Effectively, this is the bottom half of the diagram. These are features that are low-to-high value that take the least amount of effort to deliver. The misconception is that picking the features in the bottom half of this map is what teams should prioritise. It makes sense, on some levels you’re delivering immediate value to users. It’s just that often, this value is often too small to make a wholescale and enduring behavioural change. Furthermore, it is likely to be poorly orchestrated, creating a fragment product experience. Worst of all, its equates outputs with outcomes and is usually done to assuage the needs of stakeholders in other parts of the organisation.

Secondly, this is hit and miss. There is no strategic approach here as there is no identification of value or of any user behaviour(s) you’re looking to change. We’re making stuff blindly hoping that things improve. Ironically teams could deliver all of these features but still not make zero substantial improvements for their users.

Why do teams do this? Lots of reasons..a few that sprang to mind include Tight deadlines, specific ‘deliverables’ have been promised upfront, KPI’s that reframed to deliver a feature, not an outcome, and often someone in the org has sold something and the teams need to fulfil that promise.

Mapping Opportunities

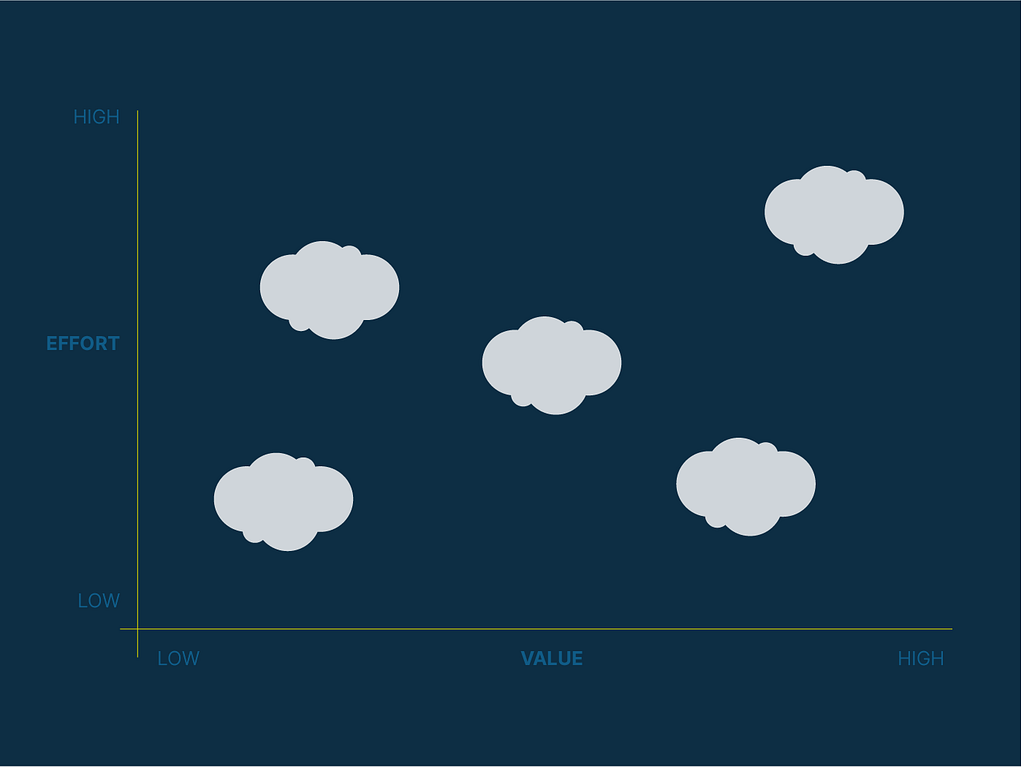

So what happens if you map areas of opportunity across the same two-axis? It yields similar results.

However, unlike the areas dominated by ‘low hanging fruit,’ we should aim to build what we think are the areas of the highest value. It is in these areas that are most likely to yield remarkable products, products that exist in a different space and solve real user problems.

Ideally, this would be the top-right corner, areas that we believe are high value and high effort. As a friend said to me “If it was easy, everyone would be doing it!” @KarlBunyan

So we still ask the question: How can we deliver value to our users as fast as possible? And also, how can make sure we’re making the biggest impact? Remember the Agile manifesto has as a key principle that “Our highest priority is to satisfy the customer through early and continuous delivery of valuable software”.

But as I mentioned earlier, opportunities are sometimes too large in themselves. In this case, I pushed for teams to break these down (often through hypothesis generation) into more granular parts that they can deliver. Alongside this, they should cultivate a diligent focus on the outcomes you want to drive, so you know you are adding value (metrics).

Build the smallest slice of your biggest opportunities

This approach advocates building the smallest version of that first…and then keep going. So whereas ‘low hanging fruit’ represents a feature that’s easiest to deliver, looking towards outcomes and breaking them down, we seek to deliver the easiest part of what we think is the highest value. Ironically, we can almost do this at the same speed as delivering a feature classified as ‘low hanging fruit’

— —

There is always a cost in choosing to do work. By choosing one thing, you are making a choice not to do all the others. Teams can’t do everything and there is always the inverse to any action you take. That inverse is usually, what has the team chosen not to do?

Feature factories are such high-risk ventures, you can fluke success, even semi-sustained success, but if those features don’t work out, then you’ve invested time, usually at the expense of other things, like continuous discovery research.

This presentation aimed to show teams that speed of delivery does not sit in opposition to the delivery of value. Quickly choosing to deliver a feature is a product guess. And almost as quickly, one can find areas of value and look to break these down into smaller units that can be incrementally delivered. In product teams, out aim to deliver a change in outcomes (behaviours). By focusing on those and tackling these in a small, iterative way, we can deliver value as fast as tackling the ‘low hanging fruit’.

The myth of the “low hanging fruit” was originally published in UX Collective on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.

from UX Collective – Medium https://uxdesign.cc/the-myth-of-the-low-hanging-fruit-5d5d8e6aa472?source=rss—-138adf9c44c—4