Some of the problems we work on as UX researchers are simple and are easily solved by getting users in front of our product. But other problems can be complex and it’s hard to know how to start solving them. In situations like that, a simple 2×2 diagram can cut through the “what ifs”, the “how abouts” and the edge cases and provide a simple way of looking at the problem. Here are 10 examples of 2×2 diagrams to simplify UX research discussions.

Loved by management consultants, a 2×2 diagram is a simple — some might say simplistic — way of looking at a problem. You consider each of the various factors in your problem and choose two that are important and that can be classified into discrete values.

One of my favourite examples comes from Steve Jobs. When Jobs returned to Apple in 1997, he looked at the product line up and thought it a mess. There were 15 product platforms and many variants of each one. He wanted to simplify Apple’s product line, so in 1998 he presented a four-quadrant product grid at the Macworld Expo. One axis on the grid was the platform (Desktop / Portable). The other axis was the market segment (Consumer / Professional). He then re-oriented Apple around creating the best possible product in each quadrant, leading to the iMac and the iBook in the consumer segments and the Power Mac and the PowerBook in the professional segments.

The problems that we deal with in product development are sometimes multi-factorial and complex. In these situations we can get swept up in discussions of technical issues or business rules and forget the importance of users and their goals. If you find that happening in your next meeting, turn to the whiteboard and try using one of these diagrams to simplify the problem and keep user needs in the forefront of the discussion.

How to decide what user groups to research with first

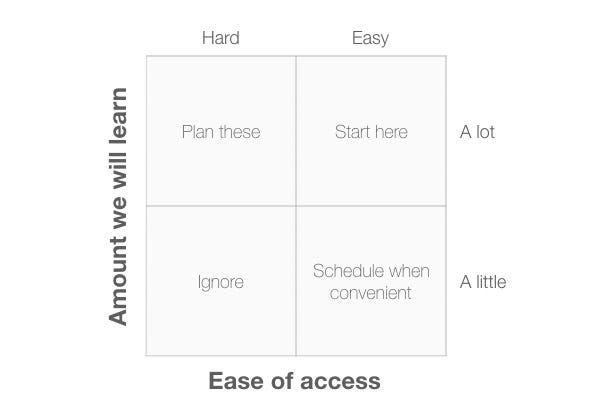

When we think of all the different user types for our product or service, it can sometimes seem overwhelming. It’s not clear where we should start our research. When I find a team in that position, I sketch out Diagram 1. The vertical axis is the amount we will learn (or expect to learn) by visiting a particular user group. Some user groups will teach us a lot about how they work in the product domain and there are others that we may already know much about. The horizontal axis is how easy or difficult it is to get to that user group. Some groups are simple to find (they may be in the same town as us) whereas others may be difficult to access because of factors like their geographical location or work schedule.

The four quadrants are:

- Ignore: User groups in this quadrant are hard to get to and will teach us little, so we can ignore them.

- Schedule when convenient: User groups in this quadrant are easy to get to but we won’t learn much from them. It makes sense to schedule visits to these groups only if you have some spare time between visiting the other groups of users.

- Plan these: We expect to learn a lot from these user groups, but for one reason or another they are hard to get to. We should start planning these visits to ensure we see these groups in the future.

- Start here: These user groups are easy to get to and we expect to learn a lot from them. It makes sense to start our research here as we can get going immediately and provide some real value to the development team.

How to create personas

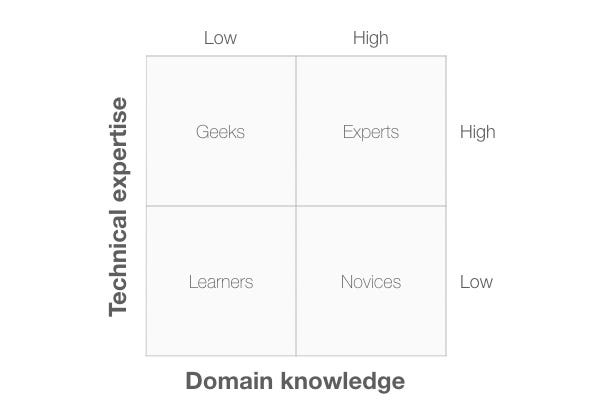

A simple way to identify personas from your research is to identify two dimensions that appear of overriding importance in your research and then to group your research participants in the appropriate quadrant. In Diagram 2, I’ve chosen two dimensions that tend to be of importance on many projects: people’s expertise with technology and their knowledge of the domain of interest.

The four quadrants are:

- Learners: This persona has low technical expertise and little domain knowledge.

- Geeks: This persona has high technical expertise and little domain knowledge.

- Experts: This persona has high technical expertise and high domain knowledge.

- Novices: This persona has low technical expertise and high domain knowledge.

Assuming you have data from field visits, you should be able to create more meaningful dimensions than these. If not, these dimensions often work well to generate assumption personas.

How to identify red routes

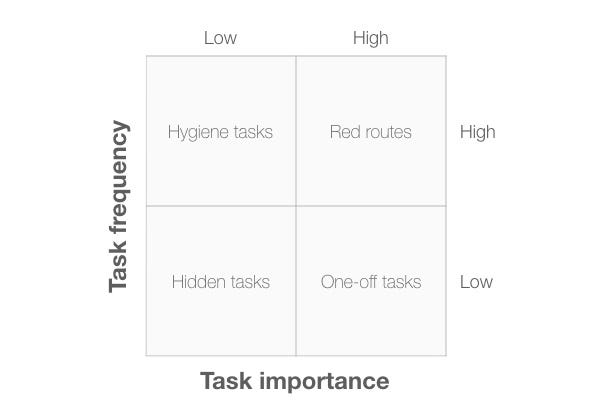

A 2×2 plot makes it easy to identify the red routes —the key tasks —that users carry out. In this example, the two dimensions are task frequency (that is, how often users carry out the task) and task importance (that is, how important the task is for users).

The four quadrants are:

- Hidden tasks: These are low frequency, low importance tasks. It doesn’t make sense to spend much time researching or optimising these tasks.

- Hygiene tasks: These are high frequency, low importance tasks: the mundane tasks (such as authentication) that users have to complete before doing what they actually want to.

- One-off tasks: These are low frequency, high importance tasks: an example might be software installation or creating an account.

- Red routes: These are high frequency, high importance tasks: we must optimise the usability of these tasks in our system.

How to decide what to fix

On completion of a usability evaluation, the development team needs to prioritise the problems so they know which ones to fix first. Diagram 4 shows a 2×2 diagram that can help here. The two dimensions are “Task frequency” (how often the task is carried out) and “Task difficulty” (how difficult the task is to complete). It makes sense to spend our time focusing on the hard, high frequency tasks.

The four quadrants are:

- Keep: These are low frequency tasks that are easy to complete. We need to make sure that any changes we make don’t have a negative effect on these tasks.

- Promote: These are high frequency tasks that are easy to complete: we should encourage marketing to make more of these when describing our product.

- Automate: These are low frequency, difficult tasks. We need to ask if there is a way to automate these tasks so that the system can do them on behalf of the user. If not, a Wizard design pattern might simplify the task for users.

- Re-design: These are high frequency, difficult tasks. Tasks in this quadrant are the ones we need to fix first.

How to choose a UX research method

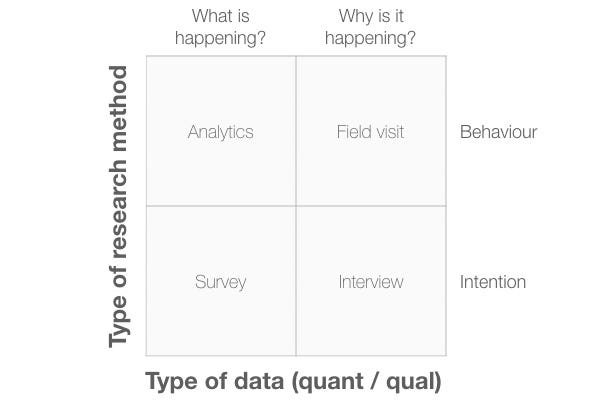

We can also use a 2×2 diagram to decide what kind of research method we should carry out. Diagram 5 shows a 2×2 diagram with “Type of research method” plotted against “Type of data”. With “Type of research method” we can classify research methods into behaviour-based methods, and intention (or opinion) based methods. With “Type of data” we can classify research methods into quantitative (“What is happening?”) and qualitative (“Why is it happening?”).

In this example, I’ve placed specific research methods in each quadrant, but these aren’t the only methods you can use. Consider these as examples only.

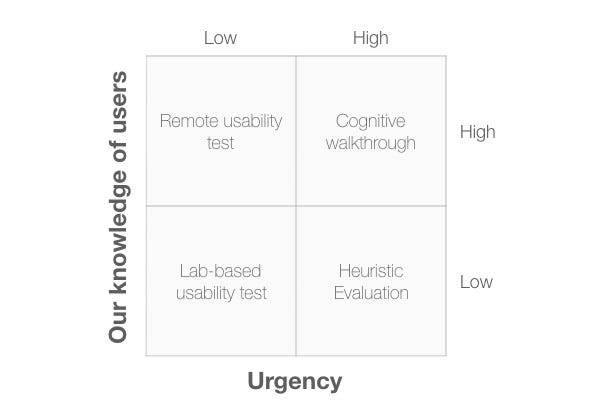

How to choose a usability evaluation method

Burrowing down further, here’s how we can use a 2×2 to choose a specific kind of usability evaluation method. One of the axes in Diagram 6 is “Our knowledge of users”. Although not an ideal situation, it’s common for product teams to not have a great deal of knowledge about users yet still have a product that they need to evaluate. In that case their knowledge of users is low. In contrast, another product team may have spent time doing field visits to users and so the team knows a thing or two about its users. The other axis is “Urgency”. Sometimes we need an answer in a day or so and other times we have the luxury of a 2-week sprint to find the answer.

This diagram helps us choose between different types of usability test and usability inspection methods.

The four quadrants are:

- Lab-based usability test: If our knowledge of users is low, a lab-based test is a good choice, especially when the test is of low urgency. By having users in the lab, we can expose the design team to users and increase their overall awareness of users and their capabilities.

- Remote usability test: When our knowledge of users is high and we have more than a few days to work on the issue, then a remote usability test is a good choice.

- Cognitive walkthrough: This inspection method makes sense when we have a good knowledge of users and it’s important to get the results urgently. This is because a cognitive walkthrough can be completed in a few hours but it does require a good knowledge of users and their tasks.

- Heuristic evaluation: This inspection method offers value when we need quick answers but don’t know a great deal about our users. Instead, we can use standardised usability principles to provide the team with a quick answer.

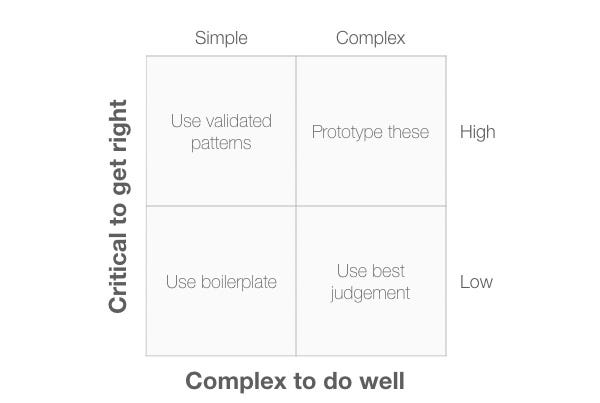

How to decide what to prototype

I’ve adapted Diagram 7 from Leah Buley’s book, The UX Team of One. It provides a useful way of deciding where, exactly, you should focus when creating a prototype. This speeds up development because you can now prototype only those aspects of the product that are both critical to get right and complex to do well.

The four quadrants are:

- Use boilerpate: Functions in this quadrant are simple to do and aren’t critical. We can use boilerplate solutions here and not spend time prototyping them.

- Use validated patterns: Functions is this quadrant are simple to do and it’s important to get them right. A good choice here would be to use an existing design pattern that we can use out of the box.

- Use best judgement: Functions is this quadrant are complex to do well but aren’t critical. We should use our judgement here of whether the function is actually needed.

- Prototype these: items in this quadrant are complex to do well and are critical to get right. It makes sense to create prototypes to explore the way these functions could be implemented and test these out with users.

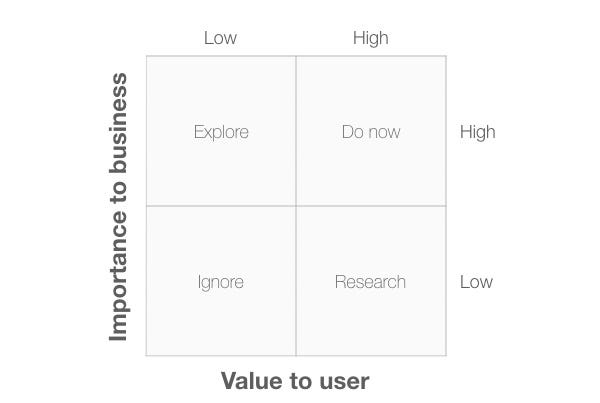

How to simplify the product backlog

The next 3 diagrams provide a useful way to simplify the product backlog by focusing on the value to users. Each 2×2 diagram has the same horizontal axis (“Value to users”).

In Diagram 8, the vertical axis is “Importance to business”. When combined with the “Value to Users” axis, this creates 4 quadrants.

- Ignore: Items in this quadrant plot low on both criteria so can be safely ignored.

- Explore: items in this quadrant are of importance to the business but offer low value to the user. We need to explore these items further to see how we can adapt them to provide user value.

- Research: items in this quadrant are important to users but of low importance to the business. We need to research these items to find out more about the value they provide.

- Do now: items in this quadrant offer value to the user and are important to the business, so it makes sense to focus on these first.

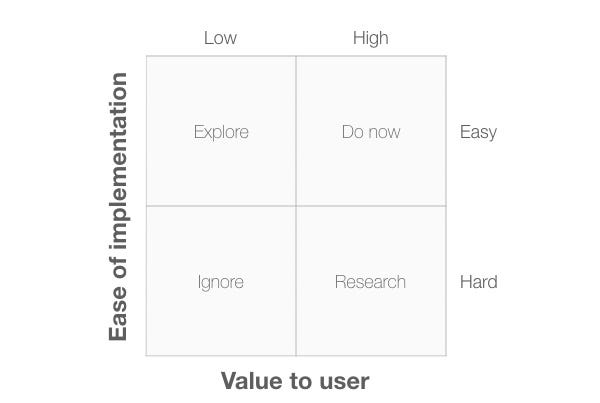

In Diagram 9, the vertical axis is now “Ease of implementation”.

The four quadrants are:

- Ignore: Items in this quadrant plot low on both criteria so can be safely ignored.

- Explore: items in this quadrant offer low value to the user but they are relatively easy to implement. We need to explore these items to see if we can adapt them to provide more user value, otherwise there is little point in working on them.

- Research: items in this quadrant are important to users but are hard for us to implement. We need to research these items to find out more about the value they provide to see if we can include some of that value in items that are easier to develop.

- Do now: items in this quadrant offer value to the user and are relatively easy to implement, so it makes sense to focus on these first.

In Diagram 10, I’ve changed the vertical axis to “Impact on revenue”. This would be an important dimension for a start up trying to identify which functions to prioritise.

The four quadrants are:

- Ignore: Items in this quadrant plot low on both criteria so can be safely ignored.

- Explore: items in this quadrant offer low value to the user but they have a high impact on revenue. We need to explore these items to see if we can adapt them to provide more user value, otherwise they won’t generate the revenue we’re hoping for.

- Research: items in this quadrant are important to users but have a low impact on revenue. We need to research these items to find out more about the value they provide to see if we can generate revenue from them.

- Do now: items in this quadrant offer value to the user and have a high impact on revenue, so it makes sense to focus on these first.

Bonus diagram: How to make an ethical design choice

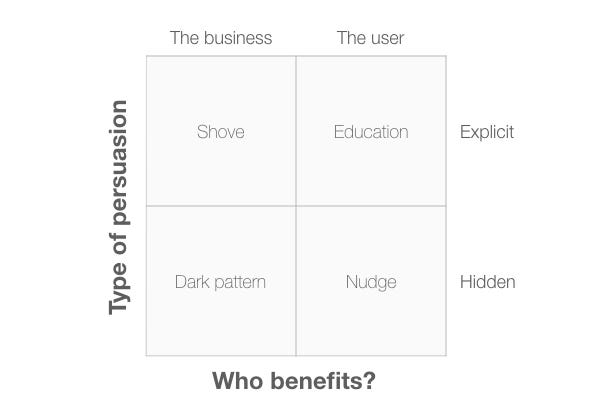

We can also use a 2×2 diagram to help us make ethical design decisions about features and workflow. In Diagram 11, the diagram has two axes, “Type of persuasion” and “Who benefits?”. Here’s how we can use it to check if we are making an ethical design choice or manipulating users.

The four quadrants are:

- Dark pattern: These are sneaky methods that attempt to manipulate the user into carrying out some action that would be of benefit to the business. A classic example of this would be a pre-checked checkbox adding someone to a mailing list if they buy a product.

- Shove: This would include more explicit methods of manipulation that encourage the user into carrying out some action that would be of benefit to the business. An example of this might be a web site that insists you sign up to their mailing list in order to receive an otherwise free report.

- Nudge: The difference between a “nudge” and a “dark pattern” is simply that the user (or society) benefits from the situation, rather than the business. An example of this might be automatic enrolment into an organ donation scheme when you apply for a driving license.

- Education: These are methods that describe a situation that is of benefit to the user, but still leave it up to the user to take action. For example, UK mobile network provider giffgaff sends its users a text at the end of each month to let them know if they should switch to another data plan, based on their previous month’s usage.

How to create your own 2x2s

Although simple, 2×2 diagrams are a useful way to simplify a complex problem into a small number of alternative choices. But they become even more powerful when you create specific diagrams based on dimensions that are particular to your users and your industry.

Be sure to keep in mind that the most useful dimensions from a UX research perspective tend to focus on the context of use: your users, your tasks and the environments they work in. Indeed, Steve Jobs’ diagram that transformed Apple did just this: its two dimensions were “users” (consumer / professional) and “environment” (desktop / portable).

Want to dive deeper into UX research? Try my book, Think Like a UX Researcher.

Originally published at www.userfocus.co.uk.

from Stories by David Travis on Medium https://medium.com/@userfocus/10-diagrams-to-help-you-think-straight-about-ux-research-aa030f7ca41c?source=rss-934fcb05e8b5——2